China is making the world more expensive

Russia’s war in Ukraine has taken a shocking toll on the region. It has also contributed to a global food crisis, as Russia is blocking vital fertilizer exports needed by farmers elsewhere, and Ukraine’s role as the breadbasket for Africa and the Middle East has been destroyed.

But there is another, unappreciated risk to global food security. China has also ordered its firms to stop selling fertilizer to other countries, in order to preserve supplies at home. Its little-noticed steps, which began last summer, were forcing farmers worldwide to leave fields fallow long before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Beijing’s moves on fertilizer are just one example of the bigger challenge facing today’s world trading system. China has become a massive producer, consumer, and trader of thousands of products, and it benefits enormously from integration into the global economy. But the way it tackled fertilizer, as well as many of its other problems, illustrates how the rest of the world suffers from its choices. China’s reflexive self-interest is too often to select the policy that sharply disrupts its trade flows, exacerbating price pressures in other countries, along with the headaches they produce.

Steel is another recent case. Until 2021, China was such an enormous supplier of metals that it was widely accused of generating overcapacity, with its low-priced exports forcing steelmakers out of business in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. Then Beijing suddenly imposed export restrictions on steel. Now, instead of contributing to a global glut, China is a steel glutton, triggering higher prices worldwide and adding more unwelcome pressures to inflation.

In still another striking reversal, Beijing increased its tariffs on pork in January, after consuming nearly 40 percent of global pork imports in 2021. Its new restrictions marked an abrupt about-face in dealing with an oversupply of pork domestically. In this case, China was worried not about inflation but about plummeting pork prices that threatened the livelihoods of its farmers.

If there were a functioning World Trade Organization (WTO), some of Beijing’s actions—especially its export restrictions—might have been found to have violated China’s legal commitments. But some likely did not, and that too is a problem. A main purpose of trade rules is to nudge large countries like China toward minimizing the international implications of their policies.

The trouble with China is that it continues to act like a small country. Its policies often have the desired effect at home—say, reducing input costs to industry or one set of Chinese farmers or by increasing returns to another. But they can also be beggar-thy-neighbor, with China selecting the policy that solves a domestic problem by passing along its cost to people elsewhere.

CHINA’S FERTILIZER EXPORT RESTRICTIONS

In 2021, Chinese and global fertilizer prices started rising, as a result of strong demand and the higher cost of energy, a key input (figure 1). China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) vowed to crack down at home. In June, it launched an investigation into the market for urea, a nitrogen fertilizer. In July, it ordered major Chinese fertilizer companies to stop exporting “to ensure the supply of the domestic chemical fertilizer market.” In October, as prices continued to rise, Chinese customs mandated dubious additional inspections. This combination of nontariff barriers led Chinese fertilizer exports to decline sharply. With more production kept at home, Chinese fertilizer prices leveled off and have since even started to fall.

Yet, the world price of fertilizer has continued to increase. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, world prices had risen to more than twice their levels of a year earlier.[1] (Before the export restrictions, China’s shares of world fertilizer exports were 24 percent for phosphates, 13 percent for nitrogen, and 2 percent for potash [see the appendix table]).

China’s decision to take fertilizer supplies off world markets to ensure its own food security only pushes the problem onto others.[2] Less fertilizer reduces the ability of farmers elsewhere to grow food. Russia’s war on Ukraine—which is a separate threat to world food supplies, as the two countries are major exporters of wheat, barley, corn, sunflowers, and other crops—means that China’s ongoing export restrictions could hardly come at a worse time. At such a critical moment, China needs to do more—not less—to help overcome the potential humanitarian challenge likely to arise in many poor, fertilizer- and food-importing countries.

Related news

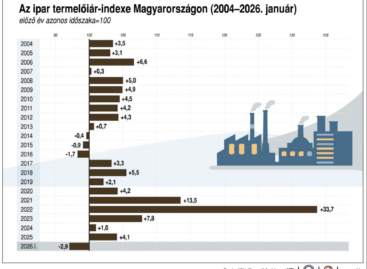

KSH: In January 2026, industrial producer prices were on average 2.9 percent lower than a year earlier and 0.9 percent higher than the previous month

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >Related news

A stable compass in the Hungarian FMCG sector for 20 years

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >There is a slice for everyone

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >