Slovakian retail between price and provenance

Slovakia’s grocery market stands at a crossroads. Inflation, politics, and structural limits have converged to test retailers’ resilience. While governments push for stronger local sourcing, retailers face shrinking margins and complex cost realities. The result is a fragile equilibrium where success depends less on price competition and more on credibility — proving local relevance in a market where “Made in Slovakia” has become both an economic and political statement.

Sebastian Rennack

international retail analyst

Aletos Retail

Slovakia’s grocers are walking a tightrope, squeezed by rising costs, limited local sourcing potential and mounting political scrutiny. Food prices sit at the heart of the country’s political debate.

Price is at the forefront

At the peak of the inflation crisis in March 2023, Slovakia recorded over 28 percent year-on-year food price inflation, the third-highest rate in the EU. Against this backdrop, policymakers have repeatedly questioned whether retailers benefit disproportionately from inflationary price rises. The government even considered new levies on large chains – all, except the cooperative Coop Jednota Slovensko, multinational retail giants.

Retailers now face mounting pressure to prove they absorbed much of the rising procurement and payroll costs to shield consumers from price hikes. For shoppers, however, the experience is straightforward: food prices rise faster than wages, making affordability a top priority.

As a first official step, the state’s pilot price comparison portal cenyslovensko.sk launched in July 2025. The site tracks roughly 700 price points across six food groups, updates daily from participating chains, lets shoppers compare by region and store format, and includes a filter to view products produced exclusively in Slovakia.

Price investments alone do not secure faster growth

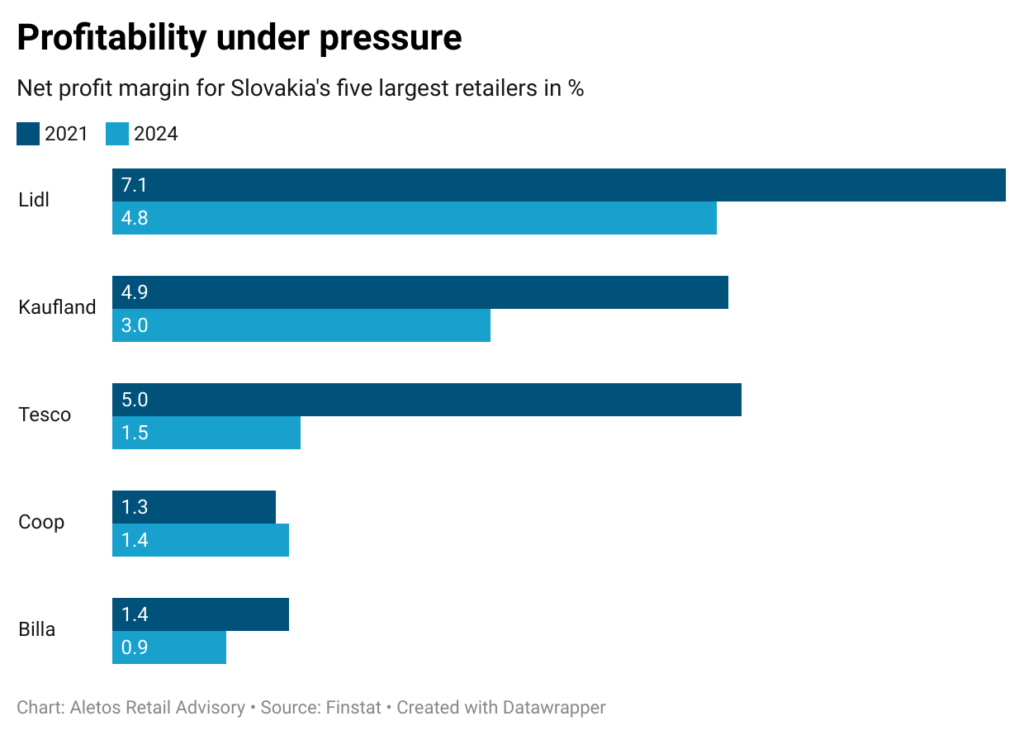

Despite heavy investment in prices, retailers have not unlocked above-average growth. Finstat data show the scale of their efforts: grocery market leader Lidl lowered its gross margin by 2.0 percentage points from 27.9 to 25.9 percent between 2021 and 2024. Kaufland’s fell by 2.6 p.p. from 28.7 to 26.1 percent, and Tesco’s from 25.6 to 25.0 percent. Yet these reductions have not translated into significantly stronger momentum than the rest of the market.

Instead, differentiation through localization appears to pay off. Local hero Coop Jednota slightly improved its gross margin from 23.3 to 23.5 percent, while Billa’s rose by the same amount to 27.2 percent, supported by its proximity and fresh convenience positioning. The impact of price investments is visible elsewhere — not in faster growth, but in thinner margins and rising operational strain.

Operational efficiency under pressure

While gross margins have narrowed, another indicator underscores the strain on profitability: productivity per employee declined sharply across all major chains between 2021 and 2024, reflecting how wage growth and store-level costs have outpaced topline gains.

Kaufland’s net profit per employee, for instance, declined from just above €9,700 per year to just over €7,300 last year, and Tesco’s plummeted from €11,300 to €4,100, underscoring that inflation’s cost impact hit retailers as well. For all large retailers the indicator has deteriorated by at least 20% over the past three years. And exception is Coop Jednota, which improved. A clear interpretation, however, is not possible, due to the cooperative’s its vertically integrated model, including own production and logistics.

In sum, Slovakia’s post-inflation equilibrium is defined not only by lower margins but also by declining labor productivity. The battle for competitiveness is fought as much on the cost side as on price or origin positioning.

Local anchoring: Creating growth opportunities beyond price

With price no longer a decisive differentiator, retailers increasingly compete on trust and local relevance — how credibly they connect to Slovak producers and communities.

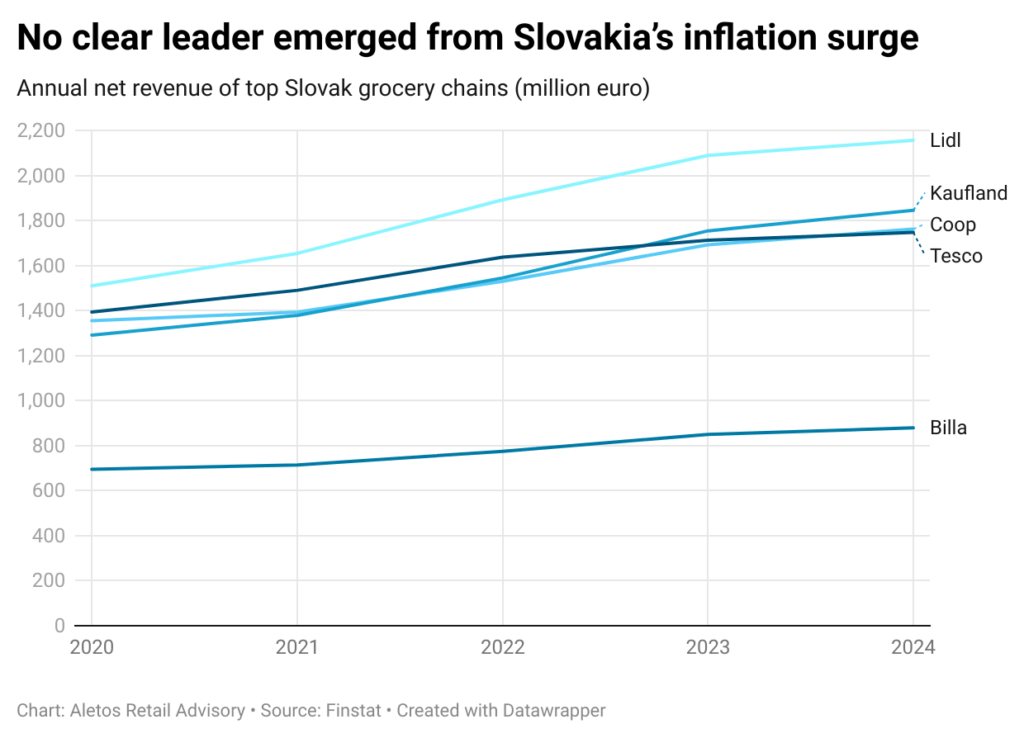

Despite cost pressure, growth paths across the top five grocery chains remain strikingly similar. Unlike in neighboring Poland, discount-oriented concepts have not managed to pull ahead of the market. Since the onset of inflation, annual net revenue growth averaged 9.2 percent for Lidl, 10.2 percent for Kaufland, 8.1 percent for Coop, and 7.2 percent for Billa, with Tesco’s hypermarket model lagging at 5.4 percent (Finstat CAGR 2021–2024). The latest 2024 data confirm this pattern of near-parallel growth.

Small country dynamics and import dependence

At the same time politicians demand more shelf space for Slovak products, which often come at a comparatively higher purchase price than in larger markets because of low domestic processing capacity and lower productivity levels. Slovakia’s food retail landscape is shaped by its position as a small Central European country with limited agricultural and production capacity. With a GDP in current prices of around 124 billion euros in 2023, Slovakia ranks 18th among the EU27 economies and cannot reach the level of self-sufficiency that larger countries enjoy. For many categories, especially processed foods, the domestic supply base remains thin.

As one reason, local analysts point to an ‘investment debt’ in the Slovak food industry: insufficient modernization, limited processing facilities, and low automation compared with neighboring Poland or the Czech Republic. The result is higher unit costs, smaller volumes, and reliance on imports to fill shelves.

This creates a dual challenge for retailers: A balancing act between the need for value and the call for local anchoring. On the one hand, there is strong political and consumer demand to highlight Slovak products, making local provenance a clear unique selling point. On the other, the structural limits of supply make it impossible to build an entire assortment on domestic goods. The situation contrasts sharply with Poland, where an estimated 80 percent of food comes from domestic production. In Slovakia, the realistic ceiling is much lower. For international chains such as Lidl, Kaufland, Tesco, and Billa, localization is less about volume and more about credibility, especially in fresh produce, meat, and sausages, where Slovak origin can be made tangible.

Local sourcing not optional anymore

Local sourcing not optional anymore

Slovakia has become a testing ground for political efforts to enforce localization. Since the mid-2010s, successive governments have sought to guarantee preferential visibility for Slovak products. Agriculture Minister Richard Takáč even proposed anchoring minimum Slovak-origin quotas in the Constitution. While the Antimonopoly Office found no evidence of excessive retail margins during the 2022–2023 inflation surge, the debate underscores how food retail has become a matter of national identity.

In this climate, local anchoring is no longer optional. Whether hypermarket, supermarket, discounter, or proximity operator, every retailer must signal credible Slovak relevance — not only through pricing, but through partnerships, sourcing, and presentation.

Related news

Péter Sebestyén is Tesco’s new Chief Operating Officer

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >Billa Pledges Fully Austrian Egg Supply For Easter

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >Two million people have already voted, so 57 million forints will be given to locals in 125 settlements, courtesy of Tesco

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >Related news

Emotions, stories, authenticity – these were the deciding factors in 2025

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >Dreher prepared messages from fathers for Women’s Day

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >IVSZ and WiTH are looking for female role models in the digital profession again this year

🎧 Hallgasd a cikket: Lejátszás Szünet Folytatás Leállítás Nyelv: Auto…

Read more >